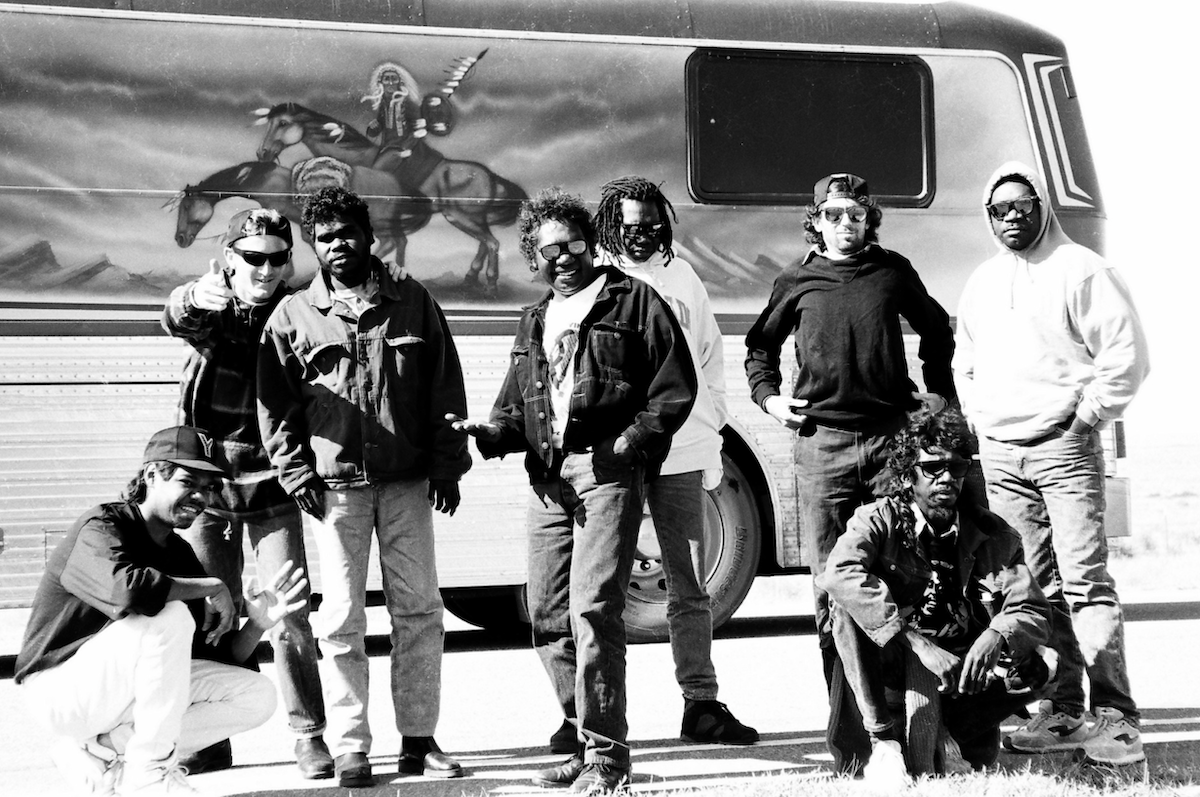

Victor & Roy Wooten: Survival, Soul and the Sound of Unity

American bassist, songwriter and record producer Victor Wooten and his brother Roy chat with The Note about their musical history, Victor’s rare neurological condition and the impact of AI on modern music.

Interview Emily Wilson // Image supplied

Not many people can say that they were opening shows with their brothers for the legendary Curtis Mayfield at the age of six - but Victor Wooten can.

The youngest of five boys, Wooten began to learn the bass when he was merely two years old. The instrument has essentially always been a part of his life.

“I’m so glad that Regi saw bass in me,” he says of his brother. “He said I had bass fingers as a kid. What eight-year-old sees their baby brother and goes, ‘those are bass fingers’?”

Now multi-Grammy Award-winners, the brothers have experienced vast, storied careers. Victor has won the Bass Player of the Year award from Bass Player magazine three times – becoming the first person in the world to win the award more than once. In 2011, he was ranked No. 10 in the Top 10 Bassists of All Time by readers of Rolling Stone magazine.

Over Zoom, Victor Wooten and his older brother Roy Wooten reminisce on their close-knit childhood. “I’m just a product of four older geniuses who saw something in me,” Victor says. “It was a great way of growing up.”

Decades later, their brotherly relations are as steadfast as ever. They continue to play together, as they always did. Victor Wooten & The Wooten Brothers have, in fact, just announced their tour of Australia, slated for February 2026, which includes a stop at Adelaide’s beloved venue The Gov.

“We just have such a long history, you know?” Roy says. “It helps to make it more fun when you’ve done it for a long time, because you don’t have to think about it so much. Now we can bring that energy of fun to the fundamentals.”

“Our parents grew up poor in North Carolina, down in the South,” Victor explains. “One of 13 and 14 siblings, in both of their families. So being poor in the South, with that many people, you can’t live together and fight. Your survival depends on everybody. So we learned that mentality of working together is more powerful than trying to work apart. Doesn’t mean that you have to agree 100% of the time. So we didn’t always agree, but we didn’t fight about it, and we still don’t.”

Success and acclaim came to the brothers early.

“I can remember at a very early age, learning that true success wasn’t dependent on what other people thought of us,” Victor says. “To quote our mom, ‘You boys are already successful, the rest of the world just doesn’t know it yet.’ And that’s a great quote to hear when you’re young.”

“We’re not competing with them, we’re slowly building on that,” Roy says of their younger selves. “We’re building on that enthusiasm that we had then. So many years later, I’m still living up to my young self that saw something with Curtis Mayfield’s conga player that showed me the future of drumming.”

“One of the things for me that really helps keep enthusiasm going is that the audience is there,” Victor explains. “I would play music without you. But I have a career playing music because of you. So every night I’m indebted to that audience for giving me this career.”

He mentions that he just texted his youngest son, who is currently at university in New York. He and his wife, who is an actor, managed to put their child through university because of bass and drama - because of the arts.

“The main thing is we’re able to do what we love to do. I had a good friend, Anthony Wellington, who said learning music is like trying to count to infinity. It doesn’t matter how long you count, you’re no closer to the end. And that’s an exciting thing - I’m not bored yet.”

He describes the bass as the “perfect” instrument for him. “The bass is all about being the floor of the building. The floor that you’re sitting or standing on is the strongest part of the building. But who complements the floor? Nobody says, ‘Thanks floor for being so strong’. That’s the real world of the bass player. And I’m fine with it.” It is rare that a bassist - often considered a background instrumentalist - achieves the kind of star status and accolades that Wooten has.

READ MORE: Drums, Power and Feminist Fire: Inside the World of La Perla

But his career hasn’t been entirely smooth-sailing. In 2018, Victor was diagnosed with a rare neurological condition called focal dystonia in his hands and upper body, causing involuntary muscular spasms, and thus challenging his ability to play.

He first noticed traces of the condition about twenty-five years ago. “I could still play, but my hands were just starting to, slowly but surely, feel a little bit sluggish. The interesting thing about it is that it got really bad the night I found out there was a name for it. Literally that night, I’m not exaggerating.”

He is pleased to report, however, that “slowly but surely” things are improving. “But I believe because it came on so slowly, over a few decades, that it’s taking a while to go away. But it’s getting there. We’ll get it to go away.”

Victor Wooten has always been a prodigy, lauded for his talents. What is it like for his talents - the talents he has built his career and his life on - to be compromised in this way?

“It’s frustrating,” he admits. “I haven’t figured this one out yet. It’s more frustrating than I want it to be.”

But there are definitely positive outcomes to it. “It’s causing me to be a student, which is really good. I have to do what I teach. I’m a beginner again. That part of it is a little bit fun because I have to practice again.”

Solemnly, his brother adds, “Sometimes in order to win, you have to lose. Sometimes in order to win, you have to let go.”

Victor nods. “I’ve always been a person who wanted to be in control of myself.” Control, however, is not constant - even for one of the world’s most technically impressive bass players.

But music - even when it is a challenge - is a constant. “Everybody in life wants to belong to something,” Victor says. Music and family - and the way that those two things are irrevocably intertwined for him - have given him that sense of belonging.

Victor, the youngest of his brothers, is now 61 (though his skin is still enviably bright and smooth). Roy is now 68. The musical landscape that they were born into, that they came of age in, that they have been part of for decades, is changing rapidly. Suffice it to say, the two brothers are not overjoyed about how things are developing.

Victor believes that talent, how good someone is at what they do, is no longer the primary concern of the industry. “The number one focus seems to be, can we market you, can we make money?” he says. “When we were younger in the ‘50s and ‘60s, the only criteria for being famous was that you were good at what you do.” He mentions Aretha Franklin and Luther Vandross. “It didn’t matter that they were heavyset, because they could sing so well. And we loved it and we would buy their records.”

He qualifies the statement. “There are still good people out there, don’t get me wrong. Some of the mainstream people are really good. But I do see the thinking of, if we can market you, you don’t have to be that good, you don’t have to be talented.”

They begin to tackle the daunting rise of artificial intelligence. Roy references the lyrics of a song by Béla Fleck and the Flecktones - a jazz fusion band that both Victor and Roy were a part of - called ‘Sojourn of Arjuna’: “He cannot jump to the absolute, he must evolve toward it.”

Roy worries that people are jumping these days, rather than taking the time to evolve - a philosophy that is at odds with what it means to create art. “Your process is being short-circuited by being able to snap your fingers.”

The journey of creation is being forgotten. “The journey is transformational,” Roy says. “All of these nuances about the soul of music can be short-circuited by AI doing it for you. There needs to be teamwork to it, there’s a journey to it, you know what I mean? There’s a cohesion: it’s not just about me being perfect, look at how good I am. It’s about your contribution to the team.”

Victor chimes in with an analogy. “It’s like if I was to go to Japan and talk to a translator - not another person, but a machine who could make me sound like I was speaking Japanese - and then say, hey, I actually can speak Japanese. It’s sort of like that.

“The good part is that this technology allows anyone to make good music. The bad part of it is that this technology allows anyone to make good music. There’s a lot of great musicians who have put in the time, who are now struggling to make a living, or to be heard.”

The whole thing, he says, is “sort of like eating fast food. It might taste just as good, but it’s not as healthy.”

These algorithms and technologies, he worries, put focus on the individual, but don’t put any focus on uniqueness or nuance. It shouldn’t be about skill, Victor believes - it should be about dedication.

“It’s who you are, it’s not how you play,” he says. “Our parents really instilled that in us: no one can be like you. So we grew up knowing ourselves and loving ourselves. People need to know that who they are, as they are, is worthy.”

Catch Victor Wooten and the Wooten Brothers at The Gov on Friday 13 February. Tickets on sale now via oztix.com.au.