Dressing To Create

Across pop culture, fashion and music are inextricably linked. Local musicians weigh in on why that might be, and on what fashion means to them.

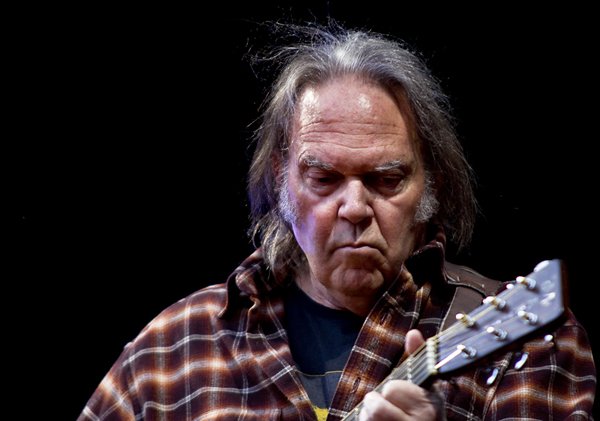

Words Emily Wilson // Image Izzie Austin

There is a manicured nature to fashion in Adelaide.

People are largely - and this is, to be fair, a generalisation based on personal observations - afraid to take risks. How you dress, how you present yourself aesthetically, is vital to the outside world’s perception of you - and, indeed, to your own perception of yourself - and often people are afraid of being perceived a certain way, of being perceived as big and bold, of being perceived as, quite frankly, too much.

When I am walking through the heart of the Adelaide CBD and observing what others around me are wearing, generally speaking, I notice that people are playing it safe. The colour palette is often muted: pastels or warm, earthy tones. The silhouettes of outfits are modest. Gently cut blazers and pale denim jeans abound. Pants are generally high-waisted to cover that scandalous strip of midriff. Perhaps it comes from being a small town historically built on middle-class propriety and conservatism - we are The City of Churches after all. A glorified country town where, in all likelihood, there are probably merely two degrees of separation between citizens. Being known by everyone doesn’t really give you the room to experiment, to try on new personalities via the fabrics you deck yourself in. There is the fear that every mistake, every instance of bold exhibitionism, every bad fashion choice, will be remembered.

Resident pop princess Aleksiah argues, “I think in certain areas there may be a conservative nature, in the more corporate kind of realm, but I think that’s a societal thing, more so a geographical thing. I know so many creative people who aren’t afraid to wear whatever they want because they don’t care how they’re perceived, that’s the kind of energy I’m learning to open myself up to.”

Rising Adelaide-based folk star Ella Ion weighs in. “I think in any tight-knit community, people can feel like they are always being perceived and might feel there is a preconceived idea from their community of who they are and how they present. I’m not really in or aware of the fashion world in Adelaide and I’m sure there are pockets that are thriving - but I don’t feel like fashion is something this city is known for.”

Musician Thea Martin, known for their involvement in Twine and Any Young Mechanic, concurs. “In bigger cities there’s just more pockets of subcultures people can align themselves with. Some cities have a real feel for how people dress, an underlying sense of style. It’s quite basic in Adelaide, which is not necessarily a problem, but I love going to places where people are more experimental with how they dress and there’s kind of a sense of fun or whimsy to how people get ready in the morning.”

There is an argument to be made for the fact that being involved in the music scene allows one to break free of these assumed restrictions. You are onstage, therefore you are leaning into the notion of being observed, therefore it is your prerogative to experiment, and to be seen as big and bold and too much. You are trying your hand at being a superstar, after all. It is a conscious, shameless decision to hog the limelight.

Luka Kilgariff-Johnson, guitarist and banjo-player in Any Young Mechanic, explains, “Compared to other facets of society, particularly younger people, there seems to be a lot less of a desire - or perhaps a need - to conform with what’s socially prevalent. I basically only hang out with musos and arts people, so I forget that most people just dress plainly and homogeneously.”

I love to watch what people wear onstage in Adelaide. There is no shortage of creativity, and the risks taken are refreshing. Artists wear pants shaped like balloons. Midriffs are flaunted - as are other expanses of sweat-flecked skin. Skirts are layered over more skirts or layered over jeans. Shirts are tight and floridly patterned, or excessively loose and floridly patterned. Maximalism is unabashedly striven for.

Across pop culture, fashion and music are inextricably interlinked. Fashion allows music to heighten itself. An outfit can make a musician an icon. Think of Prince’s frilly pirate shirt, Freddie Mercury’s designer military jacket, Stevie Nicks’s gothic accessories, Elvis Presley’s skintight jumpsuits, Courtney Love’s tattered baby-doll dresses and ripped fishnets. Sure, their music spoke for itself, they were all talented enough not to have to solely hide behind fashion, but the outer dressings helped them to secure a lasting legacy. Fashion allows music to not be just sound, but image too.

Or, as aleksiah says, “Whenever the industry you’re in relies on creativity, it spans to every part of your life and how you express yourself, including your fashion.”

“I feel like our arts scene has a thriving diversity in self-expression in fashion,” Ion says. “In a small place there are also not as many niches to fit into, and I think that allows people to just show up as they are and draw influence from outside their immediate circles. I don’t remember the last time I heard someone in my creative circle judge another person by what they’re wearing. I think we have a really healthy mentality regarding wanting people to just be themselves.”

Martin adds, “The performing aspect lends itself to more experimental or at least more considered presentation. I think when I first started playing in bands I thought about how I dressed a lot, in a way that felt stressful and scary. But the longer I was in the scene and the more I saw other people experimenting…it made me both think about it more and less. It doesn’t really feel so much like an effort now, but I do have fun with it, and I like to think about creating interesting shapes onstage, particularly being mostly the only AFAB person in the bands that I play in. I think mostly I am just trying to show that my sense of self is quite flexible and evolving. It’s less about what an outfit is for one gig, but what a series of outfits are for all the ways I show up artistically in the world.”

All musicians express the utmost importance of comfort onstage, given the physical nature of the job.

Ion adds, “The way you dress influences the way you feel about yourself. On stage or in front of the camera, you need to be able to embody the version of yourself that best reflects how you feel about your music. Because if you feel comfortable and authentic, the audience will feel comfortable and authentic in their enjoyment of your art.”

Music, so inherently abstract, is rendered more real, touchable, by clothing.

Martin explains, “Recorded music doesn’t necessarily have to have visual language. The live setting is so exciting, particularly because the visual becomes involved in the sonic. It helps to refute the idea that music or any art form is isolated from people and social and political structures and fabrics. That what you wear is somehow connected to what you play is one way to explore that.”

Aleksiah sums it all up pretty succinctly: “They’re both forms of self-expression in one way or another: we write songs because we have something to say, and we wear what we wear because it’s another way to show it. They will never not be linked in my opinion.”

“Charlie Porter makes a point in his book What Artists Wear, that visual artists tend to care about the way they dress just as much as the work they create, whether it be purely for function or to act as a uniform, to be able to enter into a heightened state for the act of creating, just the same as one puts on their business attire to go to the office,” Kilgariff-Johnson adds. “I think it’s just as true for music. If one is performing their work, it is almost necessary to be outfitted in something that allows them to reach that heightened place of expression. For some it’s full drag a la Chappel Roan, for others, a shirt and some old shorts will do.”